Generally, little importance and attention to detail is turned to Germany’s colonial past. Most school programs and history books will point to Deutsch-Ostafrika as the main territory for German imperial expansionism in the late 19th century. Usually, the date of “possession” (Besitzergreifung) of Deutsch-Ostafrika as a subordinate colony is marked down as 1885, following the aggressive seizing of a territory twice the size of Germany under the commandment of Carl Peters.

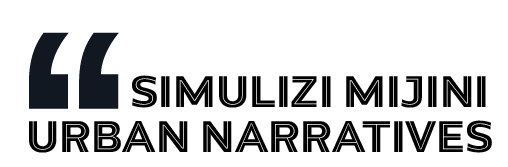

Fewer discourses acknowledge the implication of Germany in other parts of Africa –led, for the most part, by lobby groups like the Society for German Colonization (Gesellschaft für Deutsche Kolonisation, founded in 1884) and the German Colonial Society (Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft, 1887) which had vested interests in taking an active part in the scramble for Africa*. The first protectorates were established in Southwest Africa (Namibia), Cameroon, Togo, and Southeast Africa during the mid 1880s. Others were founded in the Pacific region in New Guinea, on the Marshall Islands, on a number of additional Pacific islands, and in the Chinese territory of Kiaochow around the port of Tsingtau during the late 1880s and the 1890s. Reference maps, such as the one above, which shows the state of German colonial expansion in Africa and the Far East around 1895, held particular appeal for the educated and propertied middle classes, the main supporters of colonial ventures. By contrast, the debates about colonies in the German Reichstag document that the representatives of the working classes largely opposed the domination of foreign peoples.

Colonial history in Berlin

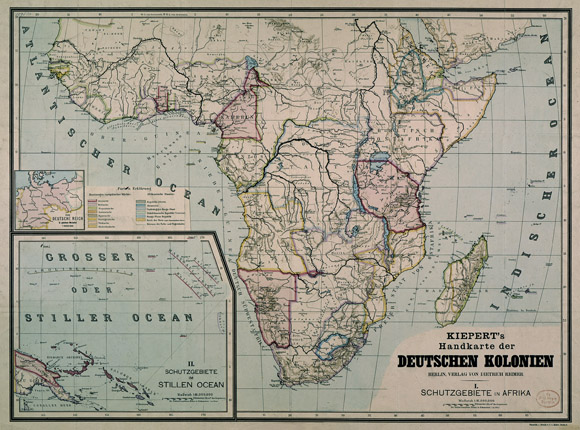

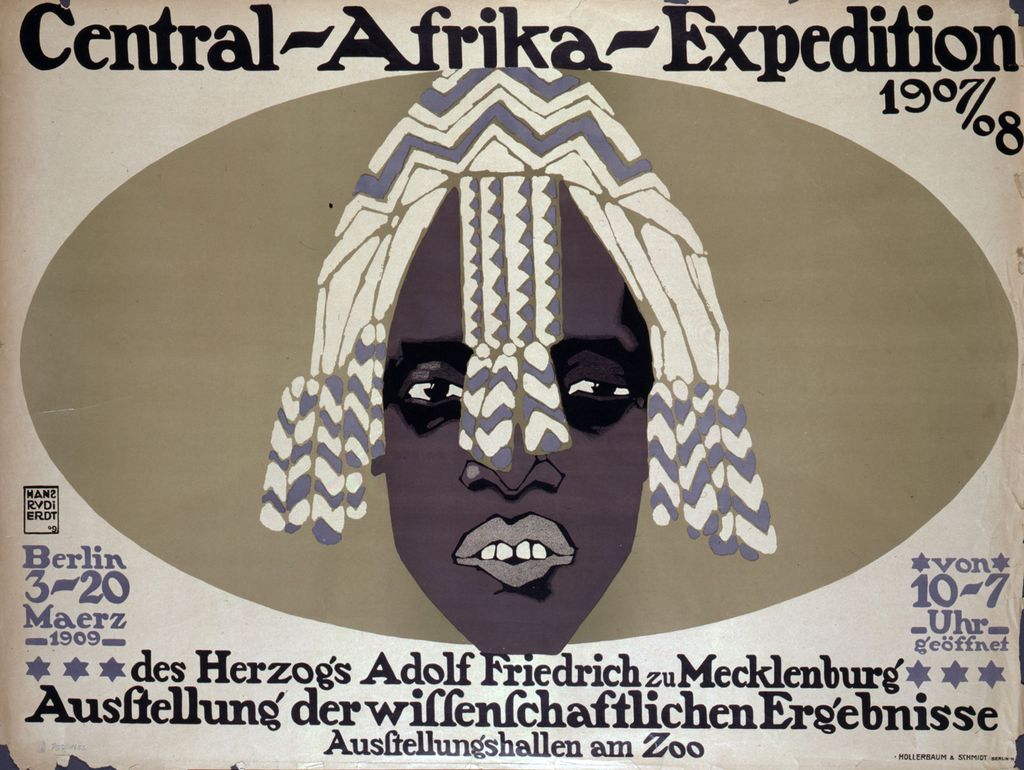

Berlin Postkolonial, an non-profit activist group has dedicated years of research and archiving to be able to answer this question. In the northeastern neighbourhood of Wedding sits a street aptly named “Afrikanische Straße”. And the surrounding street names (odonyms) all relate to the colonial and postcolonial relations of Germany and Africa, as listed on this map of the African Quarter in Berlin. We accompanied Mnyaka Sururu Mboro from Postkolonial in a tour of the area to hear about what these seemingly casual street names have implied and still represent. The designation of “Afrikanische Straße” dates back from 1906, when animal trader Carl Hagenbeck made plans to establish in Rehberge Park a permanent zoo and “Völkerschau” (human exhibition). The coercive display of “exotic creatures of Africa” had already marked the urban landscape of Berlin with the first German Colonial Exhibition held at Treptower Park in 1896. The “zoological and anthropological shows” continued until the outbreak of the first World War, bringing objects, art pieces, housing structures, plants, animals and people to Berlin –specifically to the African quarters in Wedding between 1906 and 1914.

Kopf der Wochenzeitung „Das Afrikanische (Hagenbeck) Viertel“ von 1914 (Mitte Museum Berlin, ehem. Heimatmuseum Wedding)

Traces of the past

Some decisions regarding street names are not problematic, like Ghanastraße, which was named after the country was the first to gain independence in 1958. But others are dedicated to the agents of colonial imperialism in Africa. The disturbing part, as Mboro discusses it, is that the street signs act as memorials honouring their existence but without giving any commemoration to the victims of such powers. There are no memorials for the Africans killed by German Schutztruppen in Berlin, no signs of remembrance for those who were exterminated in the Namibian concentration camps during the forgotten genocide in Swakopmund between 1904 and 1908. But the heroes of expansionism, however, still have plaques with their names in German cities –and this is one of the driving forces behind Berlin Postkolonial’s engagement to change these names and inform the public about their significance.

Wissmannstraße in Neukölln directly refers to Hermann von Wissmann, who served in the brutal colonial crusades of Belgian king Leopold II in Congo and who became the Reichkommissar for German East Africa in 1889. Part of his “accomplishments” was to suppress the indigenous opposition to their annexation. “In historical accounts, because they come from Europe, this is called the Abushiri revolt, points out Mboro. But from the other perspective, it was not a revolt: it was a defence against violent invaders. We see the memorial to Wissmannstraße in the same way. Us Blacks in Berlin, we would like to change this. Because we also live here. And while there is a street named after him, there are no memorials or”

Gröbenüfer, near Warshauer Straße, refers to Otto Friedrich von Gröben, a Brandenburger army commandant responsible for the establishment of the first German fortress in Ghana in the 17th century, from which over 30,000 were shipped off as slaves. It was renamed to May-Ayim Üfer in 2010, in honour to the Afro-German poetess and civil-rights activist. This raises a new question –should this transformation process be left visible? or should it be wiped out from historical recollection that Gröben was once a celebrated hero, who was then re-presented as a barbarous imperialist responsible for the slaughter and oppression of thousands of Africans? And when choosing to leave a trace of this transformation process, how to visualise it? In cities worldwide, the common support for stories are plaques or, in this case, a street signage; hybrids between a sharp marker and a book page, sitting upright for all to read.

A different way of dealing with the traumatic memories and stories associated to a name, is to simply “change” the referential of the name. In the Afrikanische Viertel, in 1936, a large residential road was named after Carl Peters, to whom the colonization of Tanganyika (East-Africa) is mostly attributed to. In his time, he was not actually seen as a Prussian hero; as Bismarck had vowed not to be interested in colonies, Peters received little support from the Prussian government at first. He was also known and despised for his brutal attitude towards the Africains, cumulating stories of slaughters, slave trade, land extortion under his name. The obituary found in the Singaporian Straits Times of November 1918 draws a seriously negative picture of him (granted, the newspaper was run by British writers): “To obtain opportunities for this policy he employed in dealing with Europeans every artifice of treachery, and exhausted upon the native population the resources of a mind morbidly fertile in cruelty. With the evidence which later years have brought to light before us it cannot fairly be said that Peters was a more infamous scoundrel than some other German administrators in Africa, but his crimes were too disgusting for the saner section of German opinion”. Yet later on, his status as a conqueror was restored during the Nazi regime based on his role in creating the Society for German Colonisation (Gesellschaft für Deutsche Kolonisation, which he founded in 1884 to support his expansionist agenda), and in the Pan-German League (Alldeutschen Verband), which promoted among others, social Darwinism, “racial hygiene”, and anti-semitism.

In Tanzanian memory, he is known as Mikono wa Damu –the one with blood on his hands. In 1986, the street was rededicated following an anti-colonial campaign from local residents –yet its name actually did not change. It was simply redirected to another Peters, Dr. Hans Peters, who was an administrator and politician in Berlin in the 1940s and 50s. Interestingly, this transformation is only made visible with the small plaque that’s been added on top of the Petersallee sign, like a footnote justifying the ongoing usage of the name.

Petersallee in the Afrikanische Viertel (Wedding), dedicated to colonial explorer Carl Peters in 1936. In 1986 it was decided to “rededicate”…

…The street remained Petersallee: now dedicated to CDU-politician Dr. Hans Peters, instead of colonial imperialist Carl Peters. An extra plaque was all it took.

In Trauma and memory in the city: from Auster to Austerlitz, Graeme Gilloch and Jane Kilby evoke the rapidly changing streetscape of Kurfürstendamm as observed by S. Kracauer in 1932:

“On the Kurfürstendamm – and it is not insignificant that this is a locus of consumption, fashion and leisure – the new eradicates the old seemingly without residue, and it does so with greater rapidity. […] the past is consigned to oblivion by the present, and, perhaps most importantly, how it may fleetingly reappear as an irruption that disturbs, gives a shock to, today’s passer-by. There both is, and is not, a palimpsest of forms in this sense. The trace – that which remains in the present – is not architectural, it is not in the city as such; rather, it is in Kracauer’s memory of this space. And it is ironically precisely the act of obliteration – the present absence of the former cafés – that brings them so vividly to mind. Demolition, erasure, brings with it a sudden appreciation of what is no longer there.” (in Urban memory: history and amnesia in the modern city, ed. Mark Crinson, 2005).

But what happens when, instead of a place we have seen and been into and got used to, the traces that we do want to make visible in the city belong to a history which is indirect and distant for most residents?